Planning in Context

Local stakeholder interests and expectations

One of the keys to success in planning is to ensure that the different stakeholders are involved in ways that are appropriate to their interests and communications to the various stakeholder groups before and during the planning process is of utmost importance. Rather than talking about stakeholders in a general way, it is helpful to identify more specifically who these stakeholders are and in what domain – or sphere of influence – they operate. There are four primary domains defined in the Sanitation21 planning approach [please also refer to table 1]:

- Household domain – The private sphere within which households make decisions about their behaviours and investments to improve sanitation facilities. The household domain also includes landlords who are responsible for the facilities in rented properties.

- Community domain – This is the level at which communities are collectively involved in planning activities but also involves local level political administrators and providers of services within communities.

- City domain is the level at which services are centrally planned and organised, and financial decisions are taken. The primary actors in this domain are the local authority and governmental bodies or the utility responsible for the planning, development and provision of sanitation services.

- National or provincial domain – Institutions and organisations from outside of the city such as ministries defining policy, regulation and strategies which determine practice on the ground and influence city level decision-making.

The political economy and the enabling environment

The political economy of sanitation refers to the social, political, and economic processes and actors that determine the extent and nature of sanitation investment and service provision. Understanding and managing the political economy of sanitation consists of identifying and addressing stakeholder interests and institutional determinants of sanitation investment process and outcomes (World Bank 2011). In this context, it is therefore important to consider the factors that contribute towards the enabling environment for sustainable sanitation service provision [see Figure 2].

Experiences from different countries show that city level planning initiatives are much more likely to be successful if they are undertaken where there is a higher level support from national or state government. It highlights the fact that, if the national legislation and the regulatory framework that governs the delivery of sanitation services are not well formulated, then it becomes difficult to design projects that result in sustainable improvements to service delivery.

Activities and initiatives at the local level

An important consideration is the interface between city sanitation planning and activities going on at the local level. Whereas city level planning is more strategic, covering the whole area under the jurisdiction of the local authority making use of formalized planning procedures, local-level initiatives focus on improvements to services in specific neighbourhoods, often as part of ward development plans.

Thus, community based planning is most relevant in informal settlements and unplanned peri-urban areas responding to local demands and dealing with problematic issues often related to lack of infrastructure, poor services and a range of concerns affecting the local community. Whereas city sanitation planning involves consultation of representatives from stakeholder groups, community-based planning means that community itself holds greater responsibility for the planning process itself and the actual outcome from this process. This requires a greater interaction between community members, which may require support from experts with social planning skills to facilitate participatory decision-making.

One such community-based planning approach, which is compatible with Sanitation21, is the Community-led Total Sanitation approach [See Further Reading]. Another example is the recently developed POSAF (Planning Oriented Sustainability Assessment Framework) approach (see Starkl et al. 2013).

These community level planning activities can run in parallel to and feed into the wider city sanitation planning activities, focussing on those areas which are marginalised from the municipal systems. The process may identify areas which can be connected to the city wide services and those that require a different approach due to the specific characteristics of the settlement.

Diversity of cities

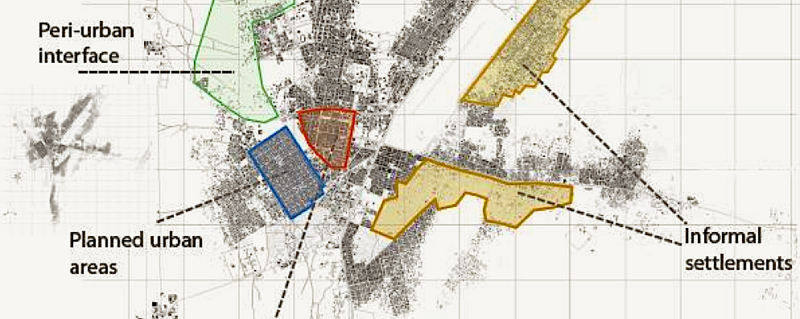

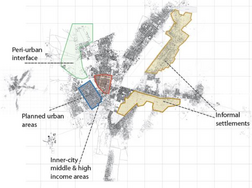

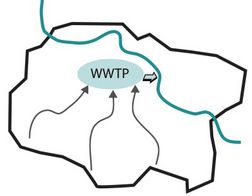

The characteristics of low-income settlements means that they are intrinsically more difficult to serve and therefore conventional service delivery approaches are often not viable. Figure 3 illustrates the varied nature of settlements in cities; highlighting that there is a need for a range of sanitation service models for different physical and socio-economic contexts.

For instance, this may be due to particular physical constraints such as low-lying ground, steep slopes, or densely packed housing with very poor access via narrow and irregular pathways. In addition there are frequently social issues compounded by poverty, which means that working in these areas requires a different approach from other parts of the city.

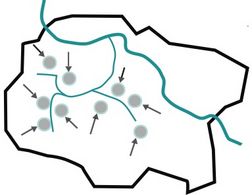

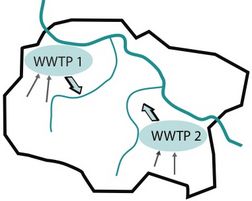

This also highlights the fact that no one type of technology will be appropriate for all areas of the city and the outcome from the application of the Sanitation21 planning approach is likely to lead towards recommendations for on-site sanitation for some areas, whereas decentralised/ semi-centralised systems or centralised sewerage may be appropriate for other areas (see Figures 4 a, b, c).

Planning within the context of available resources

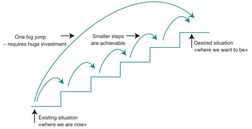

As mentioned in the introduction, city sanitation plans are often prepared with aspirational objectives, without a realistic consideration of what is actually achievable given the availability of existing resources and ignoring existing investments. The availability of financial resources for system upgrade is also often a limiting factor and therefore, a more pragmatic approach is to plan for improvements in incremental steps [see Figure 5]. Piloting, research and development should therefore be seen as part of the service delivery cycle in order to introduce locally effective innovations within an incremental approach towards improvement.

There are however situations when there is a need for a larger investment to enable a step-change in service delivery. For example, when local conditions have changed significantly over time to reach a stage when the existing facilities cannot function effectively, or where these facilities were never satisfactory in the first place. The most common situation where this is relevant is where the level of urbanization and water consumption have increased and on-site systems cannot function effectively anymore. In these situations, there is a sound argument for the installation of a sewerage system, which requires a large investment.

In making these decisions, a key consideration is to ensure that investments are cost-beneficial over the period of their asset life from start-up until the time for replacement. Potentially this may lead towards a staged approach in which a decentralised system is connected to a centralised system in the future.